Understanding Toxoplasmosis: A Zoonotic Threat in Pets and Humans

- Dr Andrew Matole, BVetMed, MSc

- Dec 15, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2024

What is Toxoplasmosis?

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), one of the most common parasites affecting warm-blooded animals, including humans and pets. It's often considered a "silent" disease due to its frequently asymptomatic nature, but it can pose serious health risks, especially for specific vulnerable populations (Dubey, 2010). In this blog post, we'll explore toxoplasmosis, how it affects pets, its zoonotic potential, and preventive measures to protect both pets and humans.

What is Toxoplasma gondii?

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular, parasitic protozoan that causes toxoplasmosis. Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled protozoan parasite that infects nearly one-third of the global population (Montoya & Liesenfeld, 2004). The life cycle of T. gondii is complex and involves two main hosts:

Definitive host: The cat family (Felidae) is the definitive host, where the parasite completes its life cycle and produces oocysts (egg-like forms) that are shed in faeces.

Intermediate hosts: Any warm-blooded animal, including humans, can be an intermediate host, where the parasite forms tissue cysts (Dubey, 2010). The parasites remain in the body as latent tissue cysts, which are commonly found in the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle.

How Do Pets Get Infected?

Pets can contract toxoplasmosis through various routes:

Ingestion of Contaminated Meat: Raw or undercooked meat containing tissue cysts can infect dogs, cats, and other pets (Tenter, Heckeroth, & Weiss, 2000).

Ingesting Oocysts: Cats can become infected by ingesting oocysts from contaminated soil, water, or food. Dogs can also ingest oocysts while scavenging or exploring contaminated environments (Dubey, 2016).

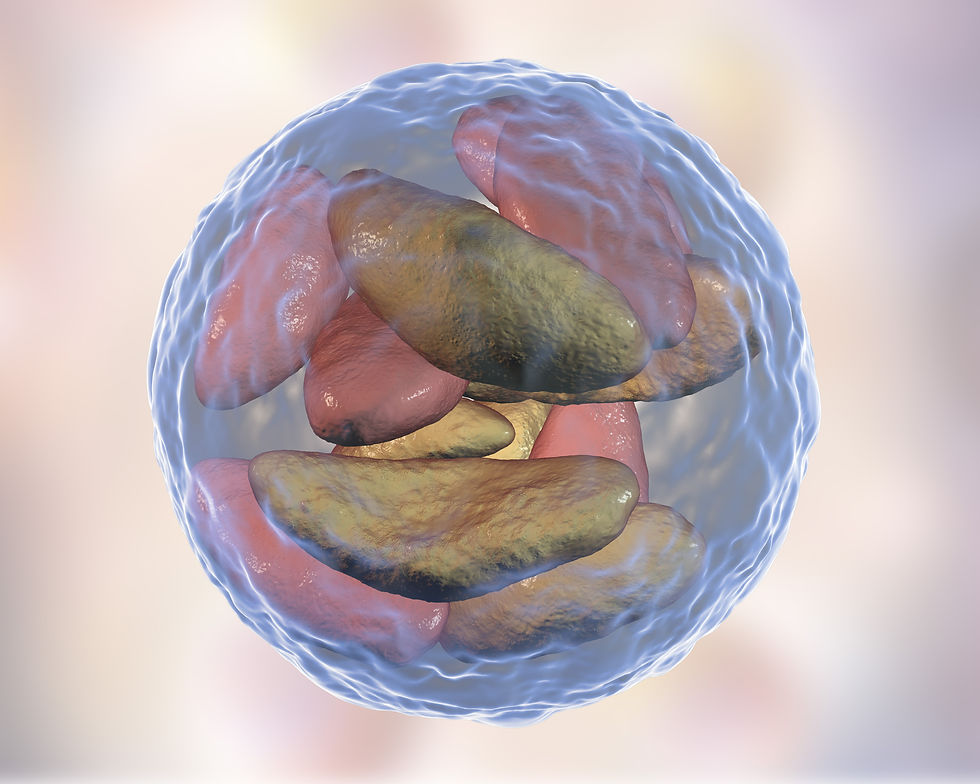

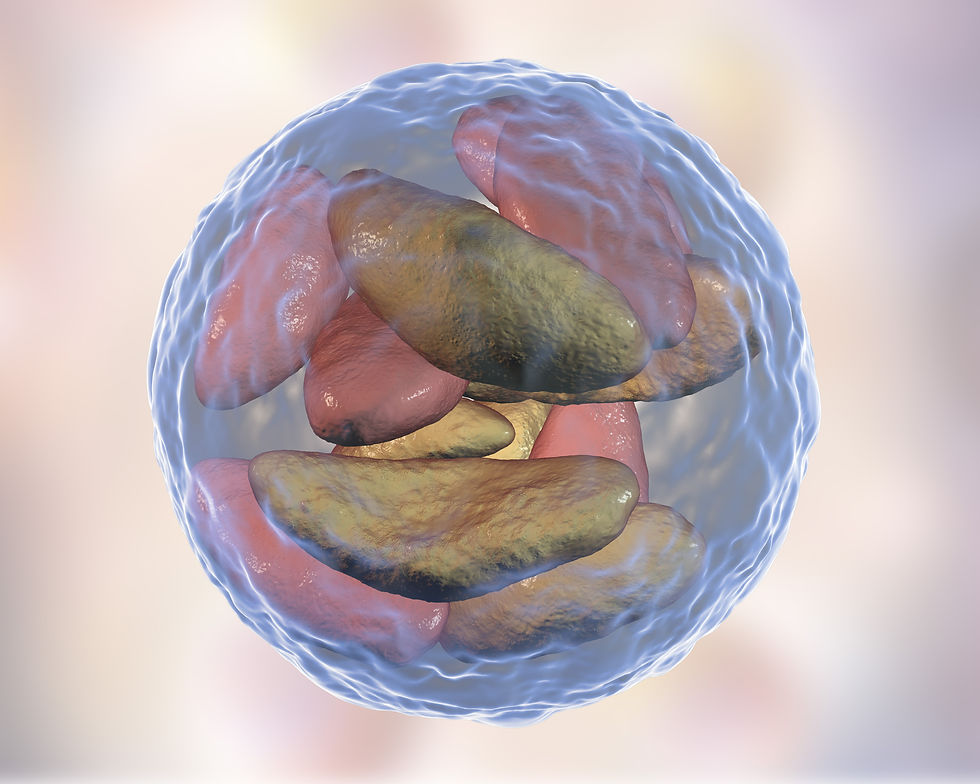

3D illustration of Toxoplasma gondii in bradyzoites stage inside tissue cyst Transplacental (vertical) Transmission: If a pregnant pet gets infected, the parasite can cross the placenta and infect the unborn offspring (Montoya & Liesenfeld, 2004).

Can Dogs Transmit Toxoplasmosis?

Dogs are not a direct source of transmission for toxoplasmosis to humans. While they can become infected with Toxoplasma gondii, they do not shed infectious oocysts in their faeces as cats do. The definitive hosts of the parasite are members of the cat family (Felidae), where the parasite completes its life cycle and produces oocysts that are shed in cat faeces (Dubey, 2010).

However, dogs can play an indirect role in the transmission of toxoplasmosis. Here's how:

Mechanical Carriers of Oocysts: Dogs can ingest oocysts from the environment (e.g., contaminated soil, water, or cat faeces) and carry these on their fur, paws, or in their mouths. If a dog comes into contact with cat faeces containing oocysts, it can spread them to the household environment or humans through physical contact (Lappin, 2014; Lindsay & Dubey, 2009).

Eating Contaminated Meat or Prey: If a dog consumes raw or undercooked meat containing T. gondii tissue cysts or hunts and eats infected prey, it can become infected. While this won't result in shedding oocysts, the dog may exhibit symptoms if immunocompromised, although such cases are relatively rare (Dubey, 2016; Sykes, 2014).

Uncooked meat Environmental Contamination: Dogs can help spread oocysts in the environment by rolling in contaminated soil or faeces, potentially bringing the parasite into the home (Lappin, 2014).

Dog faeces in the environment is a risk to kids Sexual transmission: In dogs, there is evidence that vertical transmission also occurs sexually by semen (Arantes et al., 2009).

Clinical Signs of Toxoplasmosis in Pets

While many infected pets show no symptoms, clinical toxoplasmosis can occur, especially in young or immunocompromised animals.

Cats: May exhibit lethargy, loss of appetite, fever, respiratory signs (coughing or difficulty breathing), and neurological symptoms like tremors or seizures (Dubey, 2016). In clinically affected cats, central nervous system (CNS) involvement is nearly universal, often presenting with multifocal neurological symptoms. These can include hypothermia, behavioural changes, seizures, ataxia, blindness, anisocoria (unequal pupil sizes), torticollis (head tilt), vestibular disease, muscle hyperesthesia, and varying degrees of paresis or paralysis. CNS signs may occur alone or alongside systemic disease. In some cases, cats show signs of focal disease, such as seizures or paralysis, particularly when the spinal cord is affected (Negri, et al., 2007)

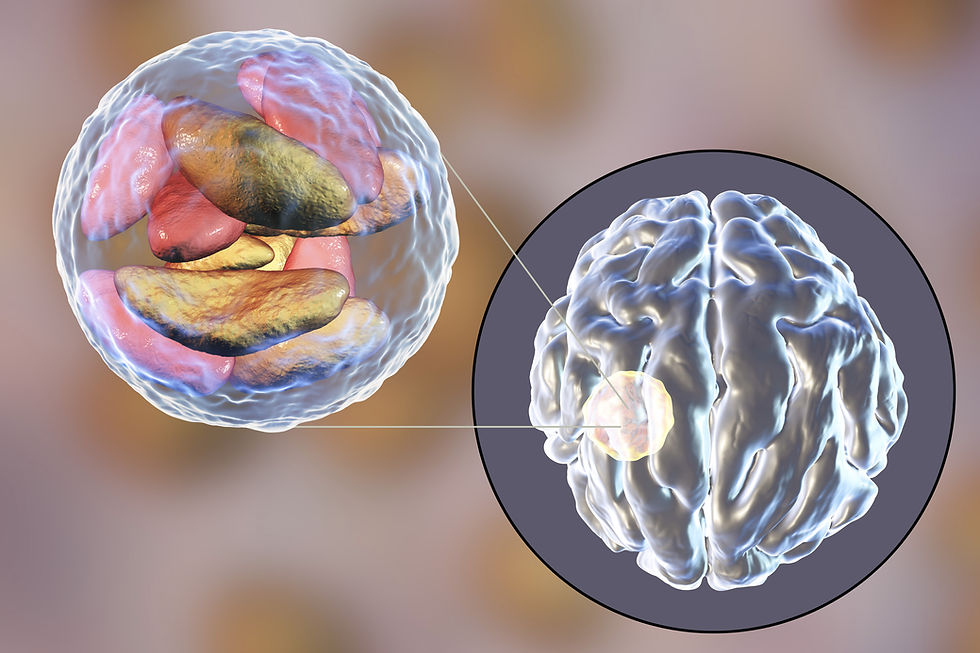

Brain abscess due Toxoplasma gondii cysts Dogs: Although less commonly affected, dogs can show symptoms similar to those seen in cats, like gastrointestinal distress (loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal Pain), jaundice, respiratory problems like shortness of breath, fever, weight loss, muscle weakness, and neurological symptoms, e.g., seizures, tremors, depression, lethargy, uncoordinated gait, partial or complete paralysis, tonsillitis (inflammation of tonsils), retinitis (inflammation of the retina), uveitis (inflammation of middle part of the eye including iris), and keratitis (inflammation of the cornea)

Zoonotic Potential: How Does Toxoplasmosis Affect Humans?

Toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans. The primary routes of transmission include:

Ingestion of Oocysts: Humans can become infected by accidentally ingesting oocysts from contaminated soil, food, or water, often by improperly handling cat litter or gardening without gloves (Hill & Dubey, 2002).

3D illustration of Toxoplasma gondii in bradyzoites stage inside tissue cyst Consumption of Undercooked Meat: Eating raw or undercooked meat from infected animals can be a significant risk factor (Tenter, Heckeroth, & Weiss, 2000).

Uncooked meat Congenital (vertical) Transmission: If a woman becomes infected during pregnancy, there is a risk of the parasite being passed to the unborn baby, potentially leading to severe congenital defects or miscarriage (Montoya & Liesenfeld, 2004).

Who is at Risk?

A Toxoplasma gondii infection may cause no symptoms or mild flu-like symptoms for most healthy people. However, specific populations are at higher risk of severe disease:

Pregnant women: Risk of congenital toxoplasmosis, which can result in birth defects (Robert-Gangneux & Dardé, 2012).

Toxoplasmosis infection in pregnant women Immunocompromised individuals: Those with weakened immune systems, such as HIV/AIDS patients or organ transplant recipients, are at greater risk for severe complications like encephalitis (Montoya & Liesenfeld, 2004).

Preventive Measures for Pet Owners

To minimise the risk of toxoplasmosis in pets and humans, the following precautions should be taken:

Proper Handling of Cat Litter: If you own a cat, clean the litter box daily since oocysts take 1-5 days to become infectious after being shed (Hill & Dubey, 2002). Pregnant women or immunocompromised individuals should avoid cleaning cat litter boxes or use gloves.

Safe Meat Handling and Cooking: Avoid feeding raw or undercooked meat to pets, and ensure the meat is cooked to safe temperatures (Tenter, Heckeroth, & Weiss, 2000).

Cooking meat Hygiene Practices: Wash hands thoroughly after handling pets, soil, or raw meat. Wear gloves while gardening.

Control of Stray Cats: Reducing exposure to stray cats can decrease the risk of environmental contamination with oocysts (Dubey, 2010).

A group of stray cats Prevent dogs from scavenging or hunting.

What Should You Do if Your Pet is Diagnosed?

If your pet is diagnosed with toxoplasmosis, work closely with your veterinarian for a tailored treatment plan, which often includes antiparasitic medications. Addressing underlying conditions that might have compromised the pet's immune system is also crucial (Sykes, 2014). For multi-pet households, consider testing other animals and reinforcing preventive measures.

Conclusion

Toxoplasmosis is a significant zoonotic disease that highlights the importance of proper pet care and hygiene practices to minimise the risk of transmission. Understanding the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii, how pets can be affected, and the measures to reduce exposure can help protect both pet and human health. While the infection is often silent, staying informed and proactive is the key to safeguarding your household against this parasitic threat.

If you suspect that your pet may have toxoplasmosis or if you are in a high-risk group, consult with a veterinarian for guidance. Taking the proper precautions can go a long way in preventing the disease and ensuring the well-being of pets and their human companions.

References

Arantes, T. P., Lopes, W. D. Z., Ferreira, R. M., Pieroni, J. S. P., Pinto, V. M., Sakamoto, C. A., & da Costa, A. J. (2009). Toxoplasma gondii: Evidence for the transmission by semen in dogs. Experimental parasitology, 123(2), 190-194.

Dubey, J. P. (2010). Toxoplasmosis of animals and humans (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

Dubey, J. P. (2016). History of the discovery of the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. International Journal for Parasitology, 46(12), 867-873.

Hill, D., & Dubey, J. P. (2002). Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 8(10), 634-640.

Lappin, M. R. (2014). Update on the diagnosis and management of Toxoplasma gondii infection in cats and dogs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 44(2), 433-447.

Lindsay, D. S., & Dubey, J. P. (2009). Canine toxoplasmosis: Not a direct source of human infection. Trends in Parasitology, 25(1), 5-6.

Montoya, J. G., & Liesenfeld, O. (2004). Toxoplasmosis. The Lancet, 363(9425), 1965-1976.

Negrin, A., Lamb, C. R., Cappello, R., & Cherubini, G. B. (2007). Results of magnetic resonance imaging in 14 cats with meningoencephalitis. Journal of feline medicine and surgery, 9(2), 109-116.

Robert-Gangneux, F., & Dardé, M. L. (2012). Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 25(2), 264-296.

Sibley, L. D., & Ajioka, J. W. (2008). Population structure of Toxoplasma gondii: clonal expansion driven by infrequent recombination and selective sweeps. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 62(1), 329-351

Sykes, J. E. (2014). Canine and feline infectious diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Tenter, A. M., Heckeroth, A. R., & Weiss, L. M. (2000). Toxoplasma gondii: from

Comments